Single Responsibility Principle

I think this is the most famous rule (probably because it is the first and some people did not read on). But seriously, I think it is very important.

Uncle Bob describes it as A class should have one, and only one, reason to change. What does it mean? For me, this sentence is not helpful :).

Other explanations say that a class or a function should do one thing.

But what is this “one thing”? Is user registration can be considered “one thing”? Or maybe it's more "things", because registrations include some other smaller things, password encryption, saving to the database and sending an e-mail.

Perhaps, sending an email can be considered a “one thing”? After all, it consists of many steps such as preparing the e-mail content and subject, extracting the user's e-mail address and handling the response. Should we set up a separate class for each of these activities? How far do we go with this “single responsibility”?!

I think we need to use a different object-oriented programming principle to answer this question. In 1974, the "high cohesion and low coupling" principle was described for the first time in the article Structured Design in the IBM journal.

I will try to present it in simple-to-understand examples.

Cohesion determines how much a function or class is responsible for. A simple example here would be Bob and Alice, the cook's helpers. Alice is making desserts. She needs to make a sponge cake, cream, glaze, cut the fruit and put it all together. Each of these steps consists of several others. It's an example of low cohesion. Bob's job is to peel potatoes, nothing else, it’s an example of high cohesion. Your method/class should be like Bob, do one thing.

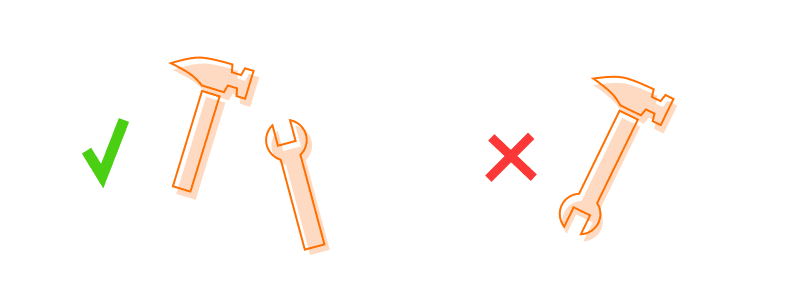

Coupling is about how easy it is to reuse a given module or class. Puzzles and Lego blocks are good examples of that. The puzzles are characterized by high coupling. One puzzle fits only in one place, it cannot be combined with other puzzles. The opposite of Lego bricks, they have a low coupling, they can be combined freely and each one can be used anywhere. Your code should be like Lego blocks, easy to use in different places.

The single responsibility principle should be used together with the high cohesion and low coupling principle. Both of these principles, in my opinion, try to say the same.

Examples

Now, an example in the PHP code. Imagine a BlogPost class:

class BlogPost

{

private Author $author;

private string $title;

private string $content;

private \DateTime $date;

// ..

public function getData(): array

{

return [

'author' => $this->author->fullName(),

'title' => $this->title,

'content' => $this->content,

'timestamp' => $this->date->getTimestamp(),

];

}

public function printJson(): string

{

return json_encode($this->getData());

}

public function printHtml(): string

{

return `<article>

<h1>{$this->title}</h1>

<article>

<p>{$this->date->format('Y-m-d H:i:s')}</p>

<p>{$this->author->fullName()}</p>

<p>{$this->content}</p>

</article>

</article>`;

}

}

What's wrong here? The BlogPost class does too many things, and as we know, it should only do one thing. The main problem is that it is responsible for printing to various formats, JSON, HTML and more if needed. Let's see how this could be improved.

We remove printing methods from the BlogPost class, the rest remains unchanged. And we're adding a new PrintableBlogPost interface. With a method that can print a blog post.

interface PrintableBlogPost

{

public function print(BlogPost $blogPost);

}

Now we can implement this interface in as many ways as we need:

class JsonBlogPostPrinter implements PrintableBlogPost

{

public function print(BlogPost $blogPost) {

return json_encode($blogPost->getData());

}

}

class HtmlBlogPostPrinter implements PrintableBlogPost

{

public function print(BlogPost $blogPost) {

return `<article>

<h1>{$blogPost->getTitle()}</h1>

<article>

<p>{$blogPost->getDate()->format('Y-m-d H:i:s')}</p>

<p>{$blogPost->getAuthor()->fullName()}</p>

<p>{$blogPost->getContent()}</p>

</article>

</article>`;

}

}

You can see a whole example of bad and good implementation here

I've seen projects where classes only have one public method with a few lines of code (usually call to a different method from a different class). Completely illegible and terrible to maintain. In my opinion, this is an example of going too far.

To sum up. Your classes and methods shouldn't be responsible for a few things. But the point here is not to go to extremes and exude absolutely everything. Just to make them easy to understand, but they also have to be consistent. So that you don't have to read them cover to cover to understand what they are doing.

Conclusion

This principle is often ignored for reasons of practicality and ease of development, but if you work on large-scale projects, it’s extremely important to respect the pillars of good OOP design, or we will lose the battle against complexity.